How Video Games Scare Us (And Why We Like It)

Some people just like to be scared. Be it Resident Evil, Amnesia: The Dark Descent, Dead Space, or Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem, horror games have long been a part of the gaming industry, offering up scares, zombies, chainsaws, and other such ilk for horror aficionados.

—

November 7, 2017

What makes a scary video game, well, scary? And why do people like being scared in the first place? Glixel talked to several game developers and academics to get a look at just what goes into making player’s hearts race, their palms sweat, and their skin crawl.

Scary science

Teresa Lynch, an assistant professor of communication technology at The Ohio State University, pointed out the big difference between fear in video games and fear in other media: Interactive engagement. And while people don’t agree if video games undermine or enhance fear experiences, the actuality seems to lie somewhere in the middle.

“I think what the research is starting to show, I mean, and this has been a popular area of academic interest in the past few years, is that it’s both,” Lynch says.

For some situations, being engaged does create a more significant fear experience. One reason for this, Lynch explained, is that while playing games players experience the psychological state of presence, which is where players feel like they are in the game. And in some of her work, she’s found that people tend to report that feelings of fear and dread lasted with them even after they stopped playing.

“For video games, because we’re actually acting in these virtual worlds, it feels much more realistic in some ways, and even if the content itself might be more pixelated or it might not be as realistic looking, we don’t necessarily have, we’re not necessarily processing that content in a way that makes it feel like it’s not real, it feels genuine to us in that immediate sense,” Lynch says.

And even though players might be well aware that the situation on screen isn’t real, that doesn’t mean that the human body is going to respond as if it were.

“There’s a perspective in human psychology that talks about this long evolution of the human brain [that] essentially does not allow us to distinguish between mediated content that we see on the screen, that we might rationally know is not real, but when we’re feeling present in that environment, and we’re engaging with the content on screen and it’s displaying behavior, our brain is going to respond to it as if it’s real,” Lynch says.

But, if people are getting scared, why do they play scary video games? What do they enjoy? Well, there is the bravery that players reported.

“One of the things that people reported as an outcome of playing a game, was mostly that they enjoyed it, and that they enjoyed it because it made them feel brave,” Lynch says.

“In video games, here we have this thing where people are saying ‘You know what, I enjoyed it because I felt brave,’ and I think that that speaks so much to the roleplaying element that video games introduce that we don’t see in other forms of content,” she added

Of course, video games have other differentiating factors from horror books, television shows, or even movies, including that players have a level of user input.

“When people are talking about what it is that scares them in games, the number one thing that they spontaneously report is having to be involved, be involved in making the decisions and playing with the controls,” Lynch says. “So, that element of being in charge of their destiny, in a fear experience, in a horrifying experience like that, is something that is influencing the responses that people have in-game environments.”

Fear, Meet Comedy

For Ian Dallas, creative director at Giant Sparrow (The Unfinished Swan, What Remains of Edith Finch), the most critical element in making a video game scary is context. Likening horror to comedy, he mentioned how the sense of surprise is vital in both genres.

Setting up that surprise for players, however, is hard. The team also found in their play tests that people’s reactions were all over the board. Again, Dallas likened it to comedy, and how jokes can land differently.

Case in point: One of the stories in Edith Finch is set in a comic book, and was inspired by 1950s EC comics and Tales from the Crypt. And while Dallas doesn’t think that Tales from the Crypt is scary, the team was surprised that some players found the in-game story unsettling.

“You just never really know how people are going to take it, until you put it in front of them and see,” Dallas says.

But, with Edith Finch, the team’s goal wasn’t to make something scary.

“The end goal was closer to creating an experience of the unknown,” Dallas says. “Like, giving players an experience of something that they had never encountered before. So, for some players, you know, that ended up being scary, and for others, it didn’t.”

Pacing is also something that the team looked at following playtests. They made the game more boring, according to Dallas, to try to let players breathe and pay attention to what was going on.

“The experience of horror or surprise or whatever are fairly intense emotions for players, so having a bit of calm is good,” Dallas says.

One part of the game — when Edith fills in the journal after each story — was added in late in development, partially just to keep players from moving.

“We don’t stop the player very often, because it’s, you know, generally frustrating for players which we’re also trying to avoid, but having these, like, just ten seconds of downtime after each story, was a way to kind of force players to catch their breath,” Dallas says.

Trust Falls

Brad Furminger is no stranger to scary things, having worked on 2002’s classic horror game Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem. Currently, Furminger works as a professor at George Brown College, while also still designing games on the side.

And regarding game design, Furminger thinks trust — and breaking that trust — is one of the significant elements that makes video games scary. Players trust designers to plop them in scenarios where they could win — and be entertained — but are also trustful that the designers have given them the necessary tools.

“Horror kind of spits in the face of that, and you want the player to feel a little bit helpless,” Furminger says. “You want them to trust you, right, so that they let their guard down, but then as soon as they kind of get into a comfortable space it’s up to us as designers to breach that trust and suddenly, you know, put them in a situation where they don’t feel like they have the tools to succeed, even though they really do.”

Horror isn’t something, by any means, unique to video games, but Furminger thinks games can do something that other genres can’t: put players directly in the shoes of the victim. He added that books could do this a bit by having inner monologues, while movies have the problem of viewer’s recognizing actors, which can cause a disconnect. Holding a controller, however, makes the experience feel more personal.

“The character in the game is trusting me to keep them safe,” Furminger says.”And that feeling of, you know, even if it’s a virtual character, they’re not real, it’s still that feeling of someone’s life is in my hands.”

And while Furminger thinks that holds true even for action adventure games like Call of Duty or Tomb Raider, “with horror, it just feels like the death is going to be worse.”

Sex and Scares

John Johanas, game director for The Evil Within 2, thinks that horror in video games comes down to a combination of factors: The mechanics, art design, and sound.

“It’s normally the story which gets you immersed into the world, and then the art that supports it, the game design that supports it, the sound that supports it, which makes you feel like you are the character in the game, and therefore the risks are real,” Johanas says.

Trent Haaga, the game’s writer — who has also worked on films such as Deadgirl, Citizen Toxie, and 68 Kill — echoed Dallas’s thoughts about horror being similar to comedy. He also sees video games as the future of the horror genre.

“There’s a lot of potential in the game format, to be able to pull off the horror that would be more difficult or more rote … if you were doing it in film,” Haaga says.

“This to me is the future of narrative, and it’s the future of horror, it’s the future of everything,” he says.

For The Evil Within 2, the team decided to take some of the feedback from the first game – players found it unrelentingly scary – and wanted a sense of ebb and flow for the sequel.

“A good comparison would be, like, have you ever ridden a roller coaster that only looped?” Johanas says. “I mean, you have to have that nice build up to the drop, right, and if you don’t have that you don’t have that anticipation and things like that, so it’s pretty much the same thing.”

Of course, fear might not be a sensation that all players enjoy feeling. But, Haada believes it is a crucial part of the human experience.

“A thousand years ago, when you were like, ‘There might be something lurking in the dark that’s going to eat me because all I have is fire and this stick,’ you probably got these things … fear is something that helped us survive for thousands and thousands of years,” Haaga says. “It’s a crucial and integral part of what it is to be a human being.”

And as society continues to get more and safer, Haaga feels that people still need to get that feeling.

“We are hard-wired to need fear because fear is what helped us survive all of this time,” Haaga says. “And now that we live in a safe place we have to create artificial things to feel that aspect of what it is to be human; you know what I mean? The drive to reproduce, the drive to avoid death and survive, are like … the only things that we’re here for.”

“People are still going to want to have sex, even if you can make babies, you know, in a test tube,” he added. “And I feel like people still want to be scared.”

Legally high horror

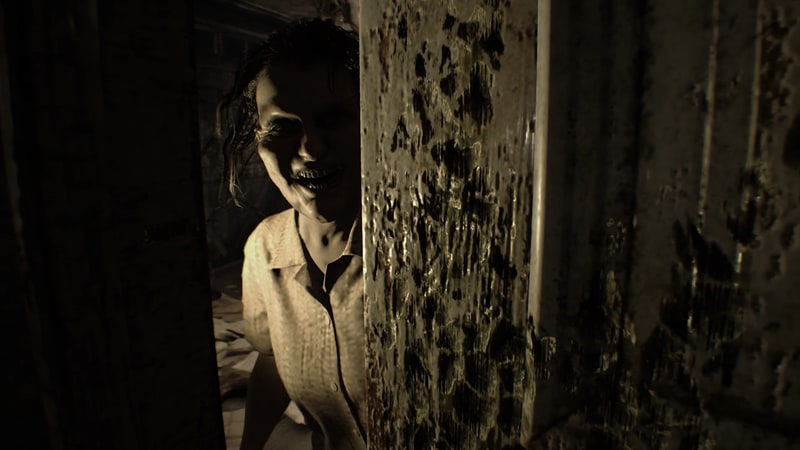

The Resident Evil series took a pruned back approach for its most recent entry — Resident Evil 7: Biohazard –which launched earlier this year.

“Instead of thinking about what we should incorporate, we thought about what we should get rid of,” Kōshi Nakanishi, who directed Resident Evil 7, tells Glixel through a translated email interview. “Things like a tenacious hero or large-scale action would detract from the scariness. Instead, we left in the things that make Resident Evil a horror game. We introduced an average character the player can empathize and feel scared with, placed them in an enclosed space to emphasize their isolation, and made ammo scarce to accentuate the tension that comes from trying to survive.”

It isn’t ideal, however, for players to be running scared all of the time, and Nakanishi also mentioned the importance of relaxing moments in between the scares.

“Constantly being scared is exhausting and not particularly satisfying,” Nakanishi says. “We worked to hone the timing of the scary parts and the breaks between them.”

Compared to other mediums, Nakanishi highlighted gaming’s interactive element, and also the relief that games can offer that isn’t part of the experience in other scary content.

By Willie Clark

Read the original article at Rollingstone.com

Recent Comments